Sailing Jellies

The evening on the bow of the ship was gorgeous, as I enjoyed a new pair of sea legs. The nearly full moon shone across an active sea, as a warm tropical breeze blew over the deck. The ocean appeared life-like, as the breaking waves sparkled in a lunar dance. Man- O-War jellies could be seen with metallic sheen sailing in the light. They were adrift on the ocean with no determined destination, no course set. Behind their fragile gelatinous bodies hides a toxic bite. Imbedded in their tentacles lie microscopic harpoons triggering upon touch a deadly neurotoxin. I am sure many creatures in the sea have learned to avoid the sting or have fallen victim to these wonders. It appears they live their lives in placid tranquility, interrupted by the occasional storm, until they meet their end upon an unforgiving shore.

The light of the moon provided the opportunity to try to catch a squid but the incandescent glow of the ship was less attractive to these denizens of the deep this night because of the illuminating affect of our only natural satellite. Watching the sea gave me time to reflect on the day. The day was filled with successes, stresses and failures, and a few worrisome moments. We managed to successfully launch the MOC1 and recover its contents without trouble, after arriving at our site sometime in the early morning hours. The net was launched before I awoke. When the net was lifted onto the deck the end buckets of the nets were dumped into transport buckets and shuttled to the wet lab, as if they were hearts awaiting a new home. Their contents were almost as well received. Photos were taken, specimens sorted, and the identifying of species began. As I write this, several taxonomists are still focused late into the night upon Petri dishes teaming with little life forms.

After the MOC1's arrival, two of the researchers were lowered over the side of the deck in a bright orange Zodiac to complete an open water collection dive. Many of the organisms are too weak to survive the plankton nets, so divers use a gentle hand to collect these specimens. This operation went off without a hitch as well. The same could not be said for the MOC25 net. It went in and climbed down smoothly, but then communication was lost and the other nets could not be opened or closed. The mission was aborted and the net retrieved. We were only able to salvage the contents of one of the eight nets. The next net to fly was the MOC10. This monstrosity was heaved over the back and it crawled down to a depth of 5000m as the ship lurked forward. This is unusually deep for a plankton net tow and the first this system has seen. All seemed to be going smoothly, then the finicky winch had technical difficulties. With an expensive piece of equipment, one the project depends upon, sitting 500m off the bottom and a stopped return, tensions were high. With a little trial and error problem solving, the system began to retrieve our precious catch, but at a much slower than planned pace. With the nets 5000 meters below and 8 miles of cable laid behind us, the hoist back to the ship will take a lengthy amount of time. We won't see our bounty until sometime tomorrow. I think my students should appreciate the fact that I am not the only science person for which things do not always go as planned. This is the nature of conducting real science.

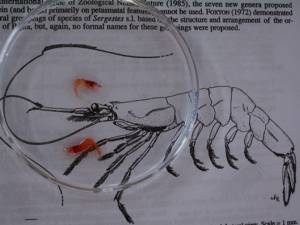

Daily Question: What phylum and class does the organism in picture one belong in?

Picture 1: Juvenile stage from a group of invertebrates

considered to me the most intelligent.

(Photo of an image generated by Russ Hopcroft)

Picture 2: Dumping plankton contents into transport buckets.

Picture 3: Setting the MOC 1 net.

Picture 4: Scientist identifying specimens.

Picture 5: Sunset over stern.

Picture 6: Identifying shrimp using a taxonomic key.

Picture 7: Examining deep water fishes.

Picture 8: Photographing natures beauty.

Picture 9: Tranquil moonlit night aboard the Ron H. Brown